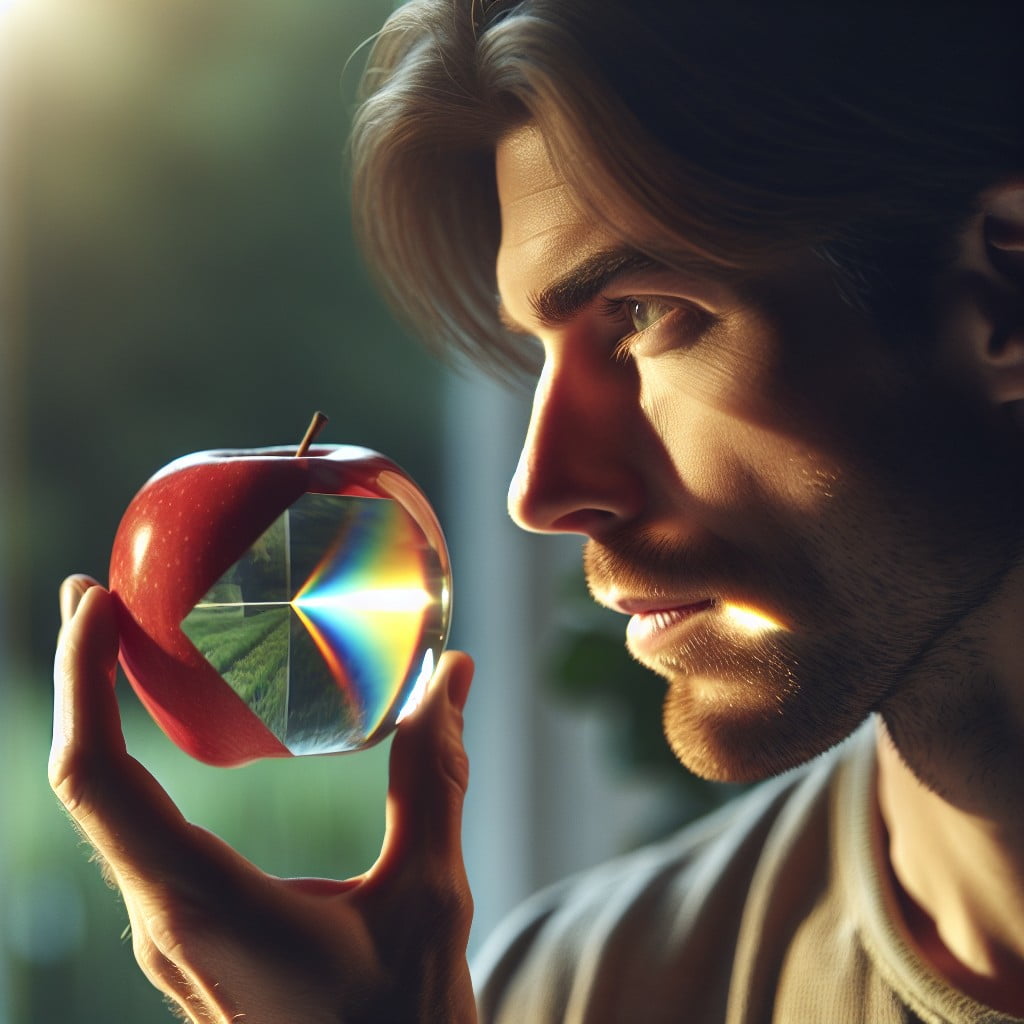

Delve into the captivating world of various levels of truth because understanding them can profoundly impact your perception and interaction with reality.

Key takeaways:

- Understanding levels of truth shapes perception of reality

- Subjective and objective truths have different criteria for verification

- First-order truths are based on immediate sensory perception

- Second-order truths involve logical reasoning and critical thinking

- Cultural and social constructs shape third-order truths

Defining Levels of Truth

Grasping the complexities of truth requires understanding its stratified nature. Truth isn’t one-size-fits-all; it’s layered, each level demanding a different approach to verification and acceptance.

- Subjective truths hinge on personal experiences and perceptions. They are individual and can differ widely from person to person.

- Objective truths, by contrast, claim universality. They’re independent of individual feelings and are often grounded in empirical evidence.

- Recognizing the variance between what is true for us personally and what is broadly accepted as truth helps navigate conflicts and misunderstandings.

- Appreciating these layers equips us to engage with the world more effectively, acknowledging others’ perspectives while critically examining our own beliefs.

Subjective Truths Vs. Objective Truths

In understanding the distinction between subjective and objective truths, it’s crucial to recognize one’s unique lens through which we view the world and the universal facts that stand irrespective of individual feelings or beliefs.

Subjective truths hinge on personal experiences, emotions, and individual perceptions. They are valid to the person holding them but not necessarily to others. A key characteristic is their variability; what may be true for one might not be for another. For instance, enjoying a specific genre of music or finding solace in the silent whispers of the forest at dusk are subjective truths.

Objective truths, by contrast, are independent of personal viewpoints. They rely on empirical evidence and can be universally verified. The existence of gravity, the need for oxygen to sustain life, and the fact that the earth orbits the sun are instances of objective truths.

It’s imperative to recognize that subjective truths shape personal realities and contribute to a rich tapestry of human experience, while objective truths form the bedrock of collective understanding, allowing for societal progress and shared knowledge. Both are critical, shaping not just how we see the world, but how we interact with it and each other.

First-Order Truths: Sensory Perception and Direct Experience

Embarking on the terrain of first-order truths, we delve into the realm of immediate reality — the raw, uninterpreted data streaming through our senses. This foundational level of truth relies on sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell to inform individuals about their environment. These truths are generally considered indisputable as they are directly experienced and less prone to debate compared to more complex types of truth.

Consider the sensation of warmth from the sun on your skin or the tart taste of a lemon — these are direct sensory experiences. They require no intermediary to verify; your lived experience is sufficient for acknowledgement. It is in this space of direct encounter that mindfulness can play a significant role, heightening our awareness to the nuances of the present moment.

Furthermore, first-order truths act as the building blocks for more abstract forms of truth. The information our senses provide is often taken as evidence in making broader assertions about the world. However, it is important to acknowledge that while our sensory experiences are considered truths, they can be subject to individual variations and limitations, making them not entirely infallible.

Second-Order Truths: Reasoned Truths Through Logical Analysis

Delving deeper than immediate perception, we engage with truths that emerge from thoughtful contemplation and analysis. This cognitive process hinges on applying logic and critical thinking to deduce, infer, or construct understanding beyond what is directly observable.

Key points illustrating this level:

- Logical Reasoning: Involves systematically processing information to arrive at conclusions, often utilizing principles of formal logic.

- Scientific Methodology: Employs hypothesis formulation, experimentation, observation, and the ability to predict outcomes, anchoring conclusions to a systematic and replicable process.

- Mathematical Proof: Abstracts reality into symbols and operations, utilizing rigorous proofs to establish irrefutable conclusions within a given set of axioms.

- Influence of Prior Knowledge: Understandings are built upon accumulated knowledge and concepts previously validated, creating a comprehensive base from which new reasoned truths can emerge.

- Critical Evaluation: Questions assumptions, scrutinizes arguments for validity, and outlines logical fallacies, honing the reliability of reasoned truths.

- Inductive vs. Deductive Reasoning: Balances generalizing from specific instances (inductive) against applying general principles to predict specific outcomes (deductive), both serving to broaden our intellectual grasp of truths.

Third-Order Truths: Constructed Truths in Cultural and Social Domains

Constructed truths emerge from the collective beliefs and norms prevalent within specific cultural and social contexts. These truths are shaped by the consensus of a group and can vary significantly from one community to another. They are often reinforced through language, ritual, and tradition.

Morality and ethics are prime examples of constructed truths, as different societies may have varying definitions of what is considered ‘right’ or ‘wrong’.

Legal systems rely on constructed truths, as laws are essentially agreed-upon principles that govern behavior and ensure societal order.

History as taught in schools represents a constructed truth, influenced by the perspective and biases of those recording and teaching it.

Money’s value is a constructed truth, agreed upon by economies and individuals who accept it as a medium of exchange.

Understanding constructed truths points to the recognition that perspectives can change, highlighting the importance of openness, empathy, and intercultural dialogue in navigating the complex tapestry of human societies.

The Role of Consensus in Establishing Truth

Consensus can act as a powerful arbitrator in distinguishing collective truths from individual interpretations. It involves the agreement of a group, often reached through discussion and compromise.

Collective Validation: When a majority share a perspective on a given assertion, it’s more likely to be recognized as a communal truth.

Scientific Consensus: The acceptance of theories, like gravity, is rooted in widespread agreement by the scientific community based on empirical evidence.

Historical Context: Over time, consensus can shift, realigning what societies deem to be true as new information and perspectives emerge.

The Court of Public Opinion: In societal matters, widespread belief can sometimes be mistaken for fact, influencing laws, norms, and societal values.

Limitations: While consensus is a guiding force, it’s fallible and doesn’t guarantee objectivity or accuracy, highlighting the importance of critical thinking and ongoing inquiry.

Limitations of Human Cognition in Discerning Truth

Human cognition, while remarkable, is inherently limited, impacting our ability to fully discern truth:

- Cognitive Biases: These are mental shortcuts that often lead us to draw inaccurate conclusions. For instance, confirmation bias causes us to favor information that supports our existing beliefs.

Memory Constraints: Our memories are fallible, subject to distortion and forgetting, which can alter our perception of truth over time.

Information Overload: The vast amount of information available today makes it challenging to process and evaluate each piece critically.

Emotional Influence: Our emotions can cloud our judgment, leading to decisions or beliefs that may not align with objective truths.

Sensory Limitations: Our senses provide a filtered experience of reality, bound by their range and sensitivity, causing potential misinterpretation of our environment.

Awareness of these limitations allows for a more critical assessment of what we consider to be true, prompting us to seek verification and consider alternative viewpoints.

The Impact of Bias and Perspective On Truth

Bias shapes our interpretation of facts, while perspective provides the vantage point from which we view truth. Bias, being an inclination or prejudice for or against one person or group, especially in a way considered to be unfair, has a profound impact on the way we process information and arrive at beliefs.

– Confirmation bias leads us to favor information that confirms our existing beliefs, often at the expense of contradictory evidence.

– Cultural bias implies that the norms and values of one’s own culture are superior, which can distort objective analysis of behaviors or beliefs of others.

– The anchoring effect causes individuals to rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered when making decisions, influencing subsequent thoughts and judgments.

Perspective is equally critical, as truth can change dramatically when viewed from different standpoints:

– In interpersonal relations, each person may have a different version of “truth” based on their unique experiences and emotions.

– In science, a shift in perspective can lead to paradigm shifts, where new truths replace old ones due to novel observations or understandings.

– In media, the angle from which a story is reported can significantly alter the perceived truth by emphasizing certain aspects over others.

Recognizing the influence of bias and perspective encourages a more nuanced and critical approach to truth, where openness to reevaluation is key.

The Evolution of Truth in the Light of New Evidence

As new evidence emerges, our understanding of what is true can change. This dynamic nature keeps knowledge in a constant state of evolution.

Scientific advancements are a prime example. Historical scientific doctrines often undergo revision when novel discoveries challenge established theories. For instance, the germ theory of disease replaced miasma theory when research demonstrated that microorganisms cause illness.

Technological progress also reshapes truth. The invention of the telescope expanded our knowledge of the universe and modified previously accepted facts about the cosmos and our place within it.

Historical reinterpretation is another reflection of truth’s evolution. New archaeological findings can alter the narrative of past civilizations and events, leading to updated history books and academic teachings.

Ethical considerations can shift societal truths. Practices once deemed acceptable may be reevaluated in the light of new moral frameworks or cultural shifts, altering social norms.

Each incremental piece of evidence has the potential to refine or overturn what we perceive as truth, demonstrating that truth is not static but a living, breathing entity, continually updated as our collective understanding deepens.

The Interplay Between Belief and Truth

Beliefs shape perceptions, often influencing how truths are interpreted and accepted. This interplay has a profound impact on both individual understanding and societal norms.

Some key points to consider in exploring this dynamic include:

- Confirmation Bias – Personal beliefs may cause individuals to seek out or give more weight to information that confirms their existing views, sometimes at the expense of opposing evidence.

- Belief Perseverance – Even in the face of contradictory evidence, people tend to cling to their initial beliefs, demonstrating the strong emotional investment in what one considers to be true.

- Paradigm Shifts – Historical examples illustrate that when a critical mass of evidence challenges the prevailing belief system, a paradigm shift can occur, altering what is widely accepted as truth.

- Cognitive Dissonance – When confronted with information that conflicts with their beliefs, individuals may experience discomfort, which can lead to either a change in belief or a rationalization to dismiss the challenging evidence.

- Faith and Spiritual Truths – These represent personal or collective truths that often exist independently of empirical evidence and are deeply rooted in individual or cultural ethos.

Understanding the complex relationship between belief and truth enhances mindfulness and enriches the practice of meditation, as it encourages an open and discerning mind.

FAQ

What are the 3 levels of truth?

The three levels of truth are, initially, when truth is subjected to ridicule, subsequently, it faces vehement opposition, and finally, it achieves recognition as self-evident.

What are the 4 levels of truth?

The four levels of truth are: objective truth, normative truth, subjective truth, and complex truth.

What are the 4 forms of truth?

The four forms of truth are objective truth, subjective truth, normative truth, and positive truth.

What are the stages of truth?

The stages of truth, as expressed by philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, consist of ridicule, violent opposition, and finally, acceptance as self-evident.

How do the levels of truth influence our perception of reality?

The levels of truth impact our perception of reality by shaping how we interpret and value different aspects of our experiences.

How can understanding the levels of truth enhance mindfulness practice?

Understanding the levels of truth can enhance mindfulness practice by allowing individuals to understand their perceptions better, and thus cultivate a more profound mindfulness, free from judgement.

In what ways do the stages of truth relate to the progression of personal spiritual growth?

The stages of truth – discovery, rejection, ridicule and acceptance – relate to personal spiritual growth as they represent the iterative process of learning, grappling with, and eventually integrating new spiritual principles into one's life.